by Esther T Bajuyo

Photo by AJ Surial

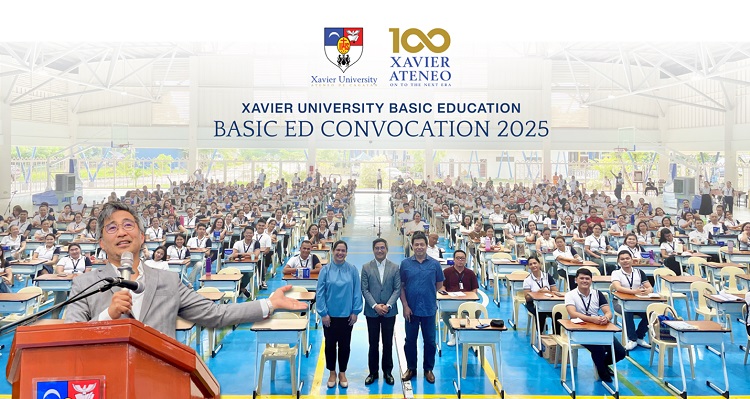

Xavier University Basic Education (XUBE) held its annual Basic Education Convocation on 23 July 2025, bringing together educators, administrators, and staff to reaffirm their commitment to fostering safe, healthy, and conducive learning environments. This year’s convocation featured an institutional training session with renowned legal expert Atty Joseph Noel M Estrada as resource speaker, focusing on student discipline and bullying.

Fostering a Collective Culture of Safety and Compassion

With a warm and engaging Welcome Remarks, Pamela Q Pajente, PhD, Vice President for Basic Education, set an inviting tone for attendees, emphasizing XUBE’s commitment to its mission of providing a safe, secure, and caring campus. Following Dr Pajente’s welcome remarks, Fr Mars P Tan, SJ, President of Xavier Ateneo, addressed the attendees with a message, underscoring the vital role of the basic education in cultivating safe spaces for learners. “Creating a nurturing environment is a collective effort. We all have a part to play in ensuring our schools are safe spaces for growth and learning,” Fr Tan emphasized.

Subsequently, unit heads introduced the new faculty and staff and congratulated the recent Teachers Licensure Exam passers, highlighting the university’s dedication to professional excellence.

Legal Lens on Student Discipline and Bullying

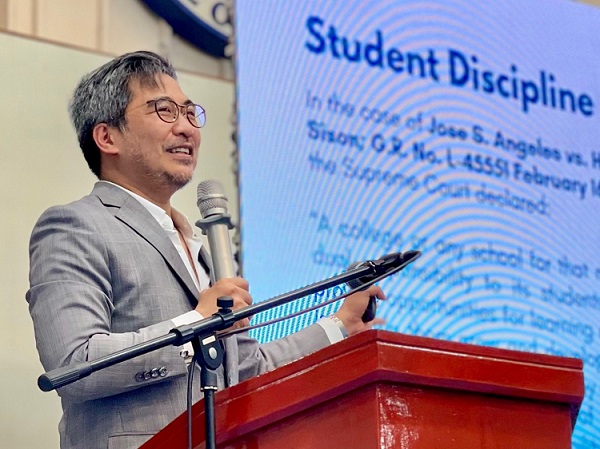

Atty Estrada’s lecture opened with a review of recent news highlighting the urgency of addressing campus violence in the Philippines. He critiqued existing measures, such as the PNP Chief’s mandate to call 911 and a senator’s proposal to install CCTV cameras in classrooms, arguing that these approaches tend to treat student violence as solely law enforcement issues, which he described as a limited perspective inconsistent with an educator’s role or that of an educator’s mindset.

“School-related violence is not solely a police matter,” Atty Estrada emphasized. “Bullies are students, too—and they need guidance, not just punishment. Our focus should be on reformative discipline that promotes both child discipline, preventing child-on-child violence or abuse, and child protection, preventing adult-on-child violence or abuse.”

Photo by AJ Surial

Key Legal Concepts and Institutional Obligations

Atty Estrada offered an in-depth discussion on several key legal principles:

Schools as “Special Parents”: Under the 1987 Philippine Constitution and Family Code, schools act in loco parentis—sharing responsibility with biological parents in ensuring student safety and proper conduct. These cases collectively reinforce the principle that schools are not only centers for learning but also legal custodians responsible for the safety, supervision, and protection of students and stakeholders under their care.

- Mother Goose Special School System, Inc v Spouses Palaganas – The Supreme Court held the school civilly liable for negligence after a student was physically assaulted by two classmates during class hours. The Court emphasized that schools have a duty of supervision and protection over students while under their custody. Failure to prevent or properly address such incidents, even among minors, constitutes a breach of duty and opens the institution to legal accountability.

- St Joseph’s College v Miranda – The school was found liable for the injuries sustained by a student during a science experiment after a heated compound exploded. The proximate cause of the injury was determined to be the teacher’s absence from the classroom during the experiment. The Court ruled that the teacher—and by extension, the school—failed in their duty of care and supervision, which directly led to the student’s injury.

- Apolinario v Heirs of Francisco de los Santos – In this case, a teacher was held principally liable for instructing a minor student to cut a plant without taking necessary precautions, resulting in an accident that led to the death of Mr de los Santos. The Court ruled that the teacher’s directive, without ensuring the student’s and bystanders' safety, amounted to negligence. The school, through its representative, was held accountable for the consequences of that action.

- St Luke’s College of Medicine–William H Quasha Memorial Foundation v Spouses Perez – The case addressed the extent of a school’s contractual obligation to maintain a safe and secure environment for students. The Court affirmed that educational institutions have a contractual duty of diligence, not only in academic instruction but also in ensuring student safety and welfare. Breaches of this obligation—whether through neglect or unsafe conditions—can give rise to legal liability.

- Saludaga v Far Eastern University – The petitioner was shot on campus by a school-hired security guard, leading to the school’s liability. The Court held that schools are vicariously liable for the actions of their agents, including security personnel, especially when harm occurs within school premises. This case underscores the duty of institutions to exercise due diligence in hiring and supervising employees to ensure campus safety.

Teachers are deemed Persons in Authority: Teachers, professors, and persons charged with the supervision of public or private schools, colleges and universities, and lawyers in the actual performance of their professional duties or on the occasion of such performance are by law deemed as persons in authority, Any person who shall attack, employ force, or seriously intimidate or resist any person in authority or any of his agents, while engaged in the performance of official duties, or on occasion of such performance shall be made liable for the crime of Direct Assault under the Revised Penal Code. This is reinforced by landmark cases such as Gelig v People of the Philippines.

Education as a Legal Contract: The school-student contract is defined at the moment of its inception — upon enrolment of the student and the obligations of the student are the following: Study well; Follow school rules and regulations, and Pay the fees. Parents shall cooperate with the school in the implementation of the school program- curricular and co-curricular. Hence, students are expected to study diligently, obey school rules, and fulfill financial obligations. Jurisprudence such as University of San Agustin v CA and Go v Letran underscores the mutual responsibilities of students and parents to uphold educational standards and cooperate with school programs. Disputes—such as parental conflicts and student protests—may impact re-enrollment decisions.

The Supreme Court has established that when relations between parents and students on one hand, and teachers and administrators on the other, have significantly deteriorated, a private school may, in the interest of the school community, require the affected students to seek enrollment elsewhere. The preservation of a morally conducive and orderly educational environment would be severely compromised if the school is compelled to admit the children of the parents involved. It can also be argued that, in such circumstances, the children may be innocent victims caught in a regrettable conflict between certain parents and the school.

Child Abuse and Physical or Verbal Maltreatment: Referencing Briñas y del Fierro v People of the Philippines, he explained that Briñas, accused of Grave Oral Defamation in relation to RA 7610, cannot be held guilty of child abuse due to the prosecution’s failure to prove the presence of specific intent to debase, degrade, or demean the victims' intrinsic worth and dignity, Briñas cannot be held guilty of child abuse. In Bongalon’s case, wherein the accused parents physically laid hands on the minors, in the midst of passionate anger and under the impression that their own children were harmed by the minor complainants, the accused were acquitted of the charge of child abuse under Section 10(a) for absence of intent to debase, degrade or demean the minors. Physical injury includes lacerations, fractured bones, burns, severe injury or serious bodily harm suffered by a child. Injuries resulting from acts of pinching, tapping, and slapping did not reach the level of physical injury, severe or serious enough as to constitute physical injuries contemplated under RA 7610. Hence, not every laying of hands on a child is child abuse.

Corporal Punishment: Inflicting corporal punishment is unlawful pursuant to Article 223 of the Family Code of the Philippines. This prohibition applies to administrators, individuals involved in child care, and all persons exercising special parental authority over students. Furthermore, such conduct is explicitly prohibited under Department of Education (DepEd) Order No 040, series of 2012, also known as the DepEd Child Protection Policy.

Positive, Non-Violent Discipline as the Norm: Positive and non-violent discipline of children encompasses a mindset and a comprehensive, constructive, and proactive approach to education that promotes the development of appropriate cognitive and behavioral patterns in children, both in the short and long term. It aims to foster self-discipline while respecting children’s fundamental human rights, recognizing them as full human beings. This approach

begins with establishing long-term objectives for students’ growth into responsible adults and leverages daily interactions and challenges as opportunities to impart essential life skills and values, thereby supporting holistic development. The 21st Century approach to student discipline should be reformative and rehabilitative rather than sole punitive measures.

Throughout his talk, Atty Estrada reiterated the importance of constructive, non-violent disciplinary methods.

“Discipline must be about growth, not fear,” he said. “Corporal punishment has no place in our schools. The law calls for discipline that is rehabilitative, rights-based, and grounded in compassion.”

He emphasized that teachers, acting as authority figures, carry significant legal and moral responsibilities, and must be equipped with knowledge of the law, empathy, and effective classroom management skills.

He also urged school administrators to exercise due diligence, particularly in vetting security personnel, to avoid institutional liability stemming from contributory negligence.

Tackling Bullying: From Policy to Practice: Atty Estrada also focused on the full implementation of Republic Act No. 10627 (Anti-Bullying Act of 2013) and its Implementing Rules and Regulations (DepEd Order No. 40, s. 2012).

These legal mandates require schools to:

- Establish Anti-Bullying and Child Protection Committees

- Implement preventive and intervention programs

- Maintain clear records of incidents and disciplinary actions

- Guarantee due process for all parties involved

- Conduct regular training for faculty, staff, and stakeholders

He detailed the many forms of bullying—psychological, emotional, cyber, social, and gender-based—noting that acts of aggression often involve power imbalances and habitual behavior. Acts of rudeness and intimidation involve unwanted physical actions such as punching, pinching, or shoving, as well as non-verbal behaviors. Non-verbal bullying can manifest through mean looks or stares.

Additionally, psychological or emotional bullying, including verbal slander, cyberbullying, and other forms of harassment, as outlined in the school’s policies, also constitute serious instances of bullying. In particular, cyberbullying through text messages, emails, chat rooms, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and other social media sites often occurs beyond school grounds and identified as a growing concern requiring digital vigilance and parental cooperation.

These situations in which the school may exercise authority over students for acts committed outside of school premises and beyond regular school hours may occur in instances such as:

a. Violations of school policies or regulations that take place in connection with off-campus, school-sponsored activities; or

b. Cases where a student's misconduct pertains to their status as a student or adversely impacts the reputation or good name of the school.

Q&A Session and Closing Reflections

The event concluded with an engaging open forum, where faculty and staff posed practical questions and shared classroom experiences. The conversation reaffirmed the community’s shared mission to foster character formation, emotional intelligence, and student accountability through a legal and ethical framework.

Photo by AJ Surial

Moving Forward: Education Rooted in Justice and Compassion

As the Philippines continues to confront the challenges of school violence and student mental health, Xavier Ateneo’s Basic Education Convocation 2025 serves as a timely and powerful reminder that safe schools are built through legal understanding, compassionate discipline, and a community-wide commitment to child welfare.

“Creating safe schools isn’t just a legal obligation—it’s a moral one,” Atty Estrada concluded. “Together, we can raise learners who are not only academically competent but also emotionally resilient and socially responsible.”